Surajit Basu finds himself viewing a thousand years of history as he stands at the Gwalior Fort, moved by the emotions of valour and honour that are enshrined here.

Bundele har bolon ke mukh hamne suni kahani thi, Khub larhi mardani woh to Jhansi wali rani thi.

The western sky is ablaze with a fiery red glow. Red and yellow flames leap to the sky, lighting up the clouds. The sun has chosen to step into its own fire, preferring to die than be dishonoured in darkness by the arriving night. Like the queens of medieval Gwalior committing jauhar in the face of certain defeat. Jauhar Kund stands today in Gwalior fort, an undying memory of that moment 800 years ago, in the midst of defeat, death, dishonour – the courage, bravery and honour of women.

The western sky is ablaze with a fiery red glow. Red and yellow flames leap to the sky, lighting up the clouds. The sun has chosen to step into its own fire, preferring to die than be dishonoured in darkness by the arriving night. Like the queens of medieval Gwalior committing jauhar in the face of certain defeat. Jauhar Kund stands today in Gwalior fort, an undying memory of that moment 800 years ago, in the midst of defeat, death, dishonour – the courage, bravery and honour of women.

It’s origin itself is shrouded in drama. A thousand years ago, Sant Gwalipa offered the wandering king , Suraj Sen, water from the Suraj Kund, and cured him of leprosy. A grateful Suraj Sen changed his name to Pal, named the city Gwalior, and built the fort here. For many generations, they held the city, till one man changed his name. Lo and behold, they lost the fort. Since then, the fort has changed many hands.

It’s origin itself is shrouded in drama. A thousand years ago, Sant Gwalipa offered the wandering king , Suraj Sen, water from the Suraj Kund, and cured him of leprosy. A grateful Suraj Sen changed his name to Pal, named the city Gwalior, and built the fort here. For many generations, they held the city, till one man changed his name. Lo and behold, they lost the fort. Since then, the fort has changed many hands.

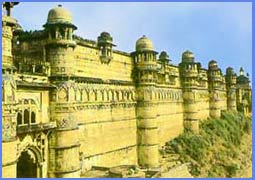

The fort at Gwalior was the key to the control of the central Indian plateau which was incorporated into a succession of states from the empire of Asoka (3rd C. BC) to that of the Moguls (16th C.), and to the 19th century British Raj. This was considered the most impregnable fortress in North and Central India. Babar called it ‘the pearl amongst fortresses in India’. The three km long sandstone hill rising abruptly a hundred meters above the surrounding plain was an ideal site to build a fortress. The outer wall of the fort is almost 3 km in length and the width varies from one km. to 200 meters. Bounded by mighty walls of solid sandstone and steep slopes, the fort encloses three temples, six palaces, several water tanks, and many other structures.

The fort at Gwalior was the key to the control of the central Indian plateau which was incorporated into a succession of states from the empire of Asoka (3rd C. BC) to that of the Moguls (16th C.), and to the 19th century British Raj. This was considered the most impregnable fortress in North and Central India. Babar called it ‘the pearl amongst fortresses in India’. The three km long sandstone hill rising abruptly a hundred meters above the surrounding plain was an ideal site to build a fortress. The outer wall of the fort is almost 3 km in length and the width varies from one km. to 200 meters. Bounded by mighty walls of solid sandstone and steep slopes, the fort encloses three temples, six palaces, several water tanks, and many other structures.

The Gwalior fort can be accessed by two roads; the preferred one for walking up is a long winding path which takes you through Urwahi Gate. As you walk up this road, huge statues of Jain Tirthankars look down upon you – a mere mortal. Carved into the cliffs of the Rock of Gwalior, these giant Tirthankars have been meditatively contemplating the world for a thousand years.

The Gwalior fort can be accessed by two roads; the preferred one for walking up is a long winding path which takes you through Urwahi Gate. As you walk up this road, huge statues of Jain Tirthankars look down upon you – a mere mortal. Carved into the cliffs of the Rock of Gwalior, these giant Tirthankars have been meditatively contemplating the world for a thousand years.

Three temples in the Gwalior Fort have provided company to the sculptures for a thousand years. Teli ka Mandir is the most famous of these. Built in the 9th century, it has a roof in the Dravidian style and its walls are profusely sculpted in the Indo Aryan style. This strange combination of two architectural styles has been the main attraction for the visitors. The highest structure within the fort is the Garuda.

Three temples in the Gwalior Fort have provided company to the sculptures for a thousand years. Teli ka Mandir is the most famous of these. Built in the 9th century, it has a roof in the Dravidian style and its walls are profusely sculpted in the Indo Aryan style. This strange combination of two architectural styles has been the main attraction for the visitors. The highest structure within the fort is the Garuda.

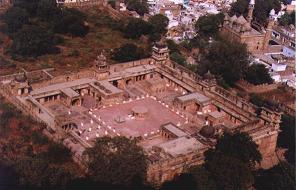

Almost as famous is the oldest temple, Sas Bahu ka Mandir. It was constructed in 11th century by Kachchwah King, Mahipala.It consists of two pillared temples which stand next to each other, one larger than the other; the larger is the mother-in-law, the smaller, the daughter-in-law! The star-shaped temples show strong resemblance to the Hoysala temples in Belur and Halebid.

A major part of the current Gwalior Fort was built by Raja Man Singh Tomar in the 15th century. The fort’s most prominent palace is the amazingly ornate Man Singh Palace, also built by Man Singh Tomar. Spread over four levels, it is embellished with stunning patterns in tile and paint. Turquoise. Yellow. Lime green. Ducks. Birds. Tigers. Most of the original tiles that adorned the exteriors have not survived; the remaining ones talk of delights beyond imagination.

A major part of the current Gwalior Fort was built by Raja Man Singh Tomar in the 15th century. The fort’s most prominent palace is the amazingly ornate Man Singh Palace, also built by Man Singh Tomar. Spread over four levels, it is embellished with stunning patterns in tile and paint. Turquoise. Yellow. Lime green. Ducks. Birds. Tigers. Most of the original tiles that adorned the exteriors have not survived; the remaining ones talk of delights beyond imagination.

In the courtyards inside Man Mandir palace, the tiles, the paint, the intricate decorations, the stone jails (filigree work in stone). Once upon a time, these were the music halls. Shielded by these screens, the royal ladies took music lessons from the maestros of those times.

Man Singh in a bid to win over the Gujar girl Mrignayani built the Gujari Mahal in the 15th century. Legend has it that the king met her – a village girl – while she was overpowering a wild bull. The king was infatuated by her beauty and strength. But she did not agree easily. She set three conditons : her own palace, a canal to bring the water of the river near her village home to the palace, and freedom to go out. The king granted her all three wishes and married her.

Man Singh in a bid to win over the Gujar girl Mrignayani built the Gujari Mahal in the 15th century. Legend has it that the king met her – a village girl – while she was overpowering a wild bull. The king was infatuated by her beauty and strength. But she did not agree easily. She set three conditons : her own palace, a canal to bring the water of the river near her village home to the palace, and freedom to go out. The king granted her all three wishes and married her.

Other palaces within the Gwalior Fort are of different eras, different architectural styles. There is the Karan Palace, the Jahangir Mahal, the Shahjahan Mahal. Each palace built by a different ruler, with his own distinctive style, each fit for a king. Each has its own tales with twists, its own legends. From each, you feel you are the monarch of all you survey.

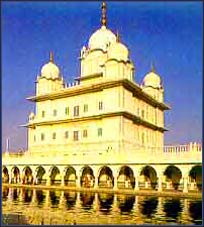

Beneath the beauty and music lie torture and death in the dungeons. Many kings used the dungeons below the palace for royal prisoners. Here, says the guide, Murad was imprisoned by Aurangzeb; here, his blood flowed. Here, Guru Govind Singh was imprisoned. The gurdwara stands in memory of that hour of religious oppression and of the final release.

Beneath the beauty and music lie torture and death in the dungeons. Many kings used the dungeons below the palace for royal prisoners. Here, says the guide, Murad was imprisoned by Aurangzeb; here, his blood flowed. Here, Guru Govind Singh was imprisoned. The gurdwara stands in memory of that hour of religious oppression and of the final release.

And there is the Jauhar Kund, which marks where the women of the royal kingdom burnt themselves to death after the defeat of the king of Gwalior in 1232.

Through this back entrance, the guide says, the Rani of Jhansi secretly entered the fort during the last days of the Indian Mutiny in 1858. It was the last bastion of Tantiya Tope and Rani of Jhansi against the British.

Through this back entrance, the guide says, the Rani of Jhansi secretly entered the fort during the last days of the Indian Mutiny in 1858. It was the last bastion of Tantiya Tope and Rani of Jhansi against the British.

“Bundele har bolon ke mukh hamne suni kahani thi,

Khub larhi mardani woh to Jhansi wali rani thi.”

She did not live to see an independent India; freedom lay in the next century. In the century after that, as we stand in Gwalior Fort, beneath the modern TV tower, we find we have travelled – through a dozen centuries, through the influence of many empires, many cultures, many architectures. Guardian of the gates to Central India, the fort is a confluence of the east and west, north and south. This is where it all met and melted: history, religion, music, architecture …I feel I have indeed journeyed to the centre of India.

Leave a Reply